Bladder Cancer

Introduction

Receiving a bladder cancer diagnosis can feel overwhelming. Remember you are not alone. Know that you will be supported by skilled medical professionals as you navigate this cancer journey. The first thing to do is learn all you can about your cancer, so you can become an active member of your health care team.

Think of your relationships with these professionals as a collaboration. You’ll be working together, and your interests are their priority. Learn all you can from reputable resources and ask your doctor questions about the cancer and its stage. Becoming an informed patient will help empower you to make the decisions that lie ahead.

Bladder Basics

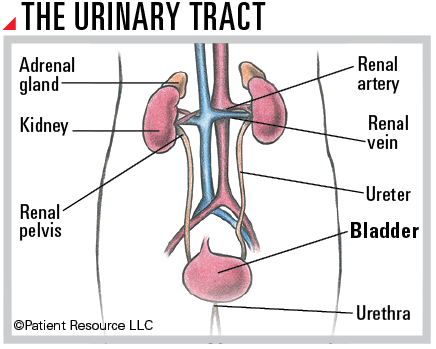

The bladder is a hollow, expandable muscular organ that is part of the urinary tract, which also includes the renal pelvis, ureters and urethra. The bladder collects and stores urine produced in the kidneys. Urine flows from the kidneys to the bladder through two thin tubes called ureters. The urinary tract is lined with urothelial cells that can change shape and stretch as the bladder expands without breaking apart.

The bladder wall is flexible, and the bladder can hold approximately two cups of urine. When it is full and you are ready to urinate, the muscles in the bladder wall contract and force the urine out of the body through a tube called the urethra.

The bladder wall is composed of four layers:

- Urothelium: Also called the transitional epithelium or mucosa, this innermost layer is composed of cells called urothelial or transitional cells.

- Lamina propria: The next layer is composed of thin connective tissue, blood vessels and nerves.

- Muscularis propria: The third layer is made up of thick muscle. Together with the lamina propria, it is also called the submucosa.

- Serosa: The outermost layer is made up of fatty connective tissue (known as perivesical fat) to help separate the bladder from nearby organs and to protect it.

Types of Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer develops when gene(s) in normal cells mutate and multiply uncontrollably. They form a disorganized mass of billions of abnormal cells called a tumor.

The most common type of bladder cancer is urothelial carcinoma, also called transitional cell carcinoma. Other forms (called histologic subtypes) of bladder cancer include squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma, all of which are almost always invasive. Distinguishing one histologic type of cancer from another is based on the appearance of the cells under a microscope.

Also important in describing bladder cancer is its form, or morphology. There are two subtypes: papillary and flat. Papillary tumors grow from the bladder’s inner lining and project toward the center of the bladder while flat tumors grow along the surface of the lining.

Bladder tumors are also described by their invasiveness:

- Noninvasive tumors have not penetrated any other layers of the bladder.

- Non-muscle invasive tumors have grown into the lamina propria but not into the muscle.

- Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) has grown into the bladder wall’s muscle and sometimes into surrounding tissues (e.g. prostate in men, known as locally advanced) or organs outside the bladder, such as the liver, lung or bone (metastatic).

Importance of a Second Opinion

Once you receive a bladder cancer diagnosis, you should be sure to see a doctor or cancer center with experience treating bladder cancer. Do not hesitate to ask your doctor for guidance in obtaining a second opinion.

Seeking a second opinion is recommended for multiple reasons. Doctors bring different training and experience to treatment planning. Some doctors may favor one treatment approach, such as a trial, while others might suggest a different combination of treatments. Another doctor’s opinion may change the diagnosis or reveal a treatment your first doctor was not aware of. You need to hear reasons and recommendations that include all your treatment options. A second opinion is also a way to make sure your pathology diagnosis and staging are accurate.

Other specialists can confirm your pathology report and stage of cancer and might suggest changes or alternatives to the proposed treatment plan. They can also answer any additional questions you have.