Bladder Cancer

Treatment Planning

Research is allowing doctors to better understand bladder cancer and how to treat it more effectively. The latest advancements in immunotherapy, targeted therapy and gene therapy are offering treatment options that may be less toxic and possibly more effective. These may have the potential to offer more people a longer and higher quality of life.

As you learn more about your diagnosis and treatment options, you are encouraged to participate in shared decision making with your medical team. Always ask questions and share your desires about your quality of life. Being informed will help you feel more comfortable moving forward. If possible, find a health care team that has experience treating people with bladder cancer.

It may also be helpful to talk to others with bladder cancer. Hearing how someone has managed a similar situation may help you adopt a positive attitude and move forward more confidently.

Treatment Options

The treatment plan your doctor creates for you will be based on many factors: whether you are newly diagnosed or are experiencing a recurrence; the presence of symptoms; your overall health; the aggressiveness of the cancer; and your goals of treatment, which may include curing the cancer, controlling tumor growth and pain, and/or improving your quality of life. Treatments can be used alone or in combination and at different times.

Keep in mind that the treatment plan you start with may change if test results or symptoms indicate the need. Your doctor will monitor you regularly, and you will be responsible for communicating with your health care team and keeping follow-up appointments. Flexibility and patience will become very important as your status changes. Think of cancer treatment as a fluid process.

Surgery is the primary method for treating a bladder cancer. Removing the tumor may offer the best chance of controlling the cancer. This is especially the case when there is no evidence of spread. Surgery may also be used to stage the cancer or to relieve or prevent symptoms that occur later. Lymph node removal (dissection) may also be necessary to stage the cancer or to control cancer that is known to have spread to the nodes. Your doctor may elect to use one or more of the following procedures:

- Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). A surgeon inserts a cystoscope through the urethra into the bladder and removes the tumor using an instrument with a small wire loop, a laser or high-energy electricity. TURBT may be used to diagnose, stage and treat bladder cancer.

- Cystectomy. A radical cystectomy removes the entire bladder and may also include nearby tissues or organs. Lymph nodes in the pelvis are also removed. In addition, men may have their prostate and urethra removed, and women may have their uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries and part of the vagina removed. A partial (segmental) cystectomy may be performed to remove only a portion of the bladder, preserving the ability to urinate normally. In some cases, a cystectomy may be done laparoscopically or robotically.

- Urinary diversion. If your bladder is removed, another way to store and pass urine is necessary. You and your treatment team will determine which of the three types of diversion will work best for you.

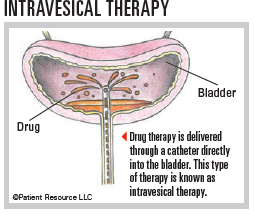

Drug therapy used to treat bladder cancer includes medications that may be given intravenously (by IV) into a vein or a port in your body, as an injection (shot) or orally as a pill. A port is a device placed under the skin, usually on the chest, that is used to draw blood and give treatments, including intravenous fluids, blood transfusions or drugs such as chemotherapy and antibiotics. Types of drug therapy used to treat bladder cancer include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, gene therapy and targeted therapy. Drug therapy may be used alone or combined with other types of treatment.

Chemotherapy may be used before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy) or after surgery (adjuvant therapy). To treat bladder cancer, chemotherapy may be given into the bladder directly (intravesically) or systemically.

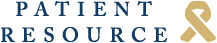

- Intravesical chemotherapy delivers drugs into the bladder through a catheter inserted through the urethra. Local treatment only destroys superficial tumor cells that come in contact with the chemotherapy solution. It cannot reach tumor cells that have invaded the muscular layer of the bladder wall or tumor cells that have spread to other organs.

- Systemic chemotherapy travels through the bloodstream.

Immunotherapy uses substances to stimulate or suppress the immune system to help the body fight cancer, infection and other diseases. Some types of immunotherapy only target certain cells of the immune system. Others affect the immune system in a general way. Types of immunotherapy used to treat bladder cancer include cytokines, immune checkpoint inhibitors, modified bacteria and some monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).

Cytokines aid in immune cell communication and may play an important role in the full activation of an immune response. They are given intravesically (directly into the bladder) for localized bladder cancer.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors help the immune system fight against cancer. They do this by blocking proteins called checkpoints that are made by some types of immune system cells. When these checkpoints are blocked, the immune system can kill cancer cells more effectively. These drugs are given intravenously. The ones approved for bladder cancer are monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which are proteins made in a laboratory that bind to the surface of immune cells to enhance the activity of the immune system against bladder cancer.

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is a weakened form of the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis that does not cause disease. BCG stimulates an immune response against bladder cancer cells and is given intravesically over multiple weeks.

Gene therapy is a new intravesical treatment option approved for patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) in whom BCG has ceased to be effective. It is a way to deliver a gene encoding interferon (a natural substance that helps the body’s immune system fight disease) into bladder cells.

The interferon then becomes a part of those cells’ DNA, causing the bladder cells to make interferon, which helps the immune system and may block bladder cancer growth.

Targeted therapy uses drugs to target specific molecules that cancer cells need to survive and spread. They work in different ways to treat cancer including:

- Stopping cancer cells from growing by interrupting signals that cause them to grow and divide

- Stopping signals that help form blood vessels

- Delivering cell-killing substances to cancer cells

- Starving cancer cells of hormones they need to grow

- Helping to directly cause cancer cells to die

The types approved for bladder cancer include a kinase inhibitor and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).

A kinase inhibitor may be used to treat some bladder cancers with a fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR2 or FGFR3) gene mutation. Data suggest that tumors with mutated FGFR3 are less likely to be recognized by the immune system, making targeted therapy an option for this gene mutation.

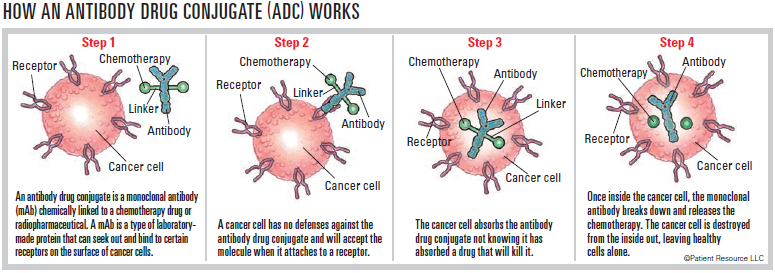

The approved mAbs are antibody drug conjugates (ADCs). The mAbs used for ADCs may be delivered via certain chemotherapy drugs directly to cancer cells expressing or displaying proteins that are more likely to be present on cancer cells. The cancer cell absorbs the ADC. Once inside the cell, the ADC releases the chemotherapy to destroy it from within.

Chemoradiation therapy (CRT) combines systemic chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which involves irradiation to the bladder and usually the adjacent pelvic lymph nodes. CRT may be considered as an alternative to surgery for muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). CRT is performed after the urologist surgically removes as much of the bladder tumor as possible through TURBT. This treatment approach is considered a bladder-preservation option because removal of the bladder may not be necessary if cancer is not detected after treatment.

Radiation therapy uses high-energy radiation to destroy cancer cells and shrink tumors. In patients with bladder cancer, high energy irradiation is given by external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) using a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. In addition to being used with chemotherapy as an alternative to surgery to cure bladder cancer, EBRT may also reduce symptoms from an advanced tumor in the bladder or from spread to another organ or to the bones.

Clinical trials are medical research studies seeking to evaluate new approaches to the treatment of a cancer. A clinical trial may offer access to new treatments not yet widely available. Let your team know whether you are open to considering a clinical trial. You can also search on your own. Once you find a potential trial, talk with your doctor.

Monitoring for Recurrence

Bladder cancer that returns after treatment is called recurrent bladder cancer. The cancer may return in the same area as the primary cancer or in a different area of the body. It can happen weeks, months or even years after treatment stops, which is why a follow-up care regimen is so important.

It is common for many bladder cancers to return after treatment and sometimes they can return multiple times. This makes diligent follow-up appointments necessary to catch a potential recurrence early. Some doctors may offer intravesical therapy after initial treatment to try to prevent a recurrence from occurring.

If your bladder cancer returns, your doctor will recommend a series of tests to determine any changes in your type of cancer, whether it has spread and physical symptoms. A new treatment plan may

be developed, and you may add finding a clinical trial to your plan. Ask your doctor about follow-up appointments to monitor for a recurrence.

Terms to Know

You will hear a lot of new terms as you learn about your cancer and its treatment options. Some of the terms your medical team uses may be confusing. These explanations may help you feel more informed as you make the important decisions ahead.

First-line therapy is the first treatment used.

Second-line therapy is given when the first-line therapy does not work or is no longer effective.

Standard of care refers to the widely recommended treatments known for the type and stage of cancer you have.

Neoadjuvant therapy is given to shrink a tumor before the primary treatment (usually surgery).

Adjuvant therapy is additional cancer treatment given after the primary treatment (usually surgery or radiotherapy) to destroy remaining cancer cells and lower the risk that the cancer will come back.

Local treatments are directed to a specific organ or limited area of the body and include surgery and radiation therapy.

Systemic treatments travel throughout the body and are typically drug therapies such as chemotherapy, gene therapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

Intravesical therapy is a type of systemic treatment that puts anticancer drugs directly into the bladder through a thin, flexible tube inserted into the urethra.

Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (MIBC) is an advanced cancer that has invaded the bladder wall or spread outside the bladder.

Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) is cancer that is confined to the lining of the bladder and does not invade the bladder wall.

Trimodality therapy is a combination of three treatments: TURBT, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

| Commonly Used Medications |

| Chemotherapy |

| cisplatin |

| doxorubicin (Adriamycin) |

| methotrexate |

| mitomycin (Jelmyto, Mitozytrex, Mutamycin) |

| thiotepa (Tepadina) |

| valrubicin (Valstar) |

| Immunotherapy |

| Cytokine |

| interferon (Roferon-A, Intron A, Alferon) |

| Gene Therapy |

| nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg (Adstiladrin) |

| Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| avelumab (Bavencio) |

| nivolumab (Opdivo) |

| pembrolizumab (Keytruda) |

| Modified Bacteria |

| Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) |

| Targeted Therapy |

| Kinase Inhibitor |

| erdafitinib (Balversa) |

| Monoclonal Antibody |

| enfortumab vedotin-ejfv (Padcev) |

| sacituzumab govitecan-hziy (Trodelvy) |

| Some Possible Combinations |

| carboplatin (Paraplatin) and gemcitabine (Gemzar) |

| cisplatin and gemcitabine (Gemzar) |

| Dose dense (DD)-MVAC (methotrexate, vinblastine [Velban, Velsar], doxorubicin [Adriamycin] and cisplatin) |

| enfortumab vedotin-ejfv (Padcev) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) |

| MVAC - methotrexate, vinblastine (Velban, Velsar), doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cisplatin |

| nivolumab (Opdivo) with cisplatin and gemcitabine (Gemzar) |

| nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln (Anktiva) with Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG) |