Leukemia

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

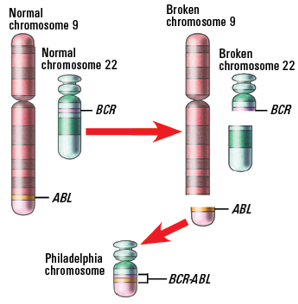

CML is a slow-growing cancer of the bone marrow and blood that begins when a genetic change mutates or damages early (immature) myeloid cells, which are the cells that become white blood cells (other than lymphocytes), red blood cells or cells that make platelets. Most people who have CML have an abnormal chromosome called the Philadelphia chromosome. It results from an abnormal fusion of two genes, BCR and ABL , which then produces the BCR-ABL protein. It is important to test for the Philadelphia chromosome or the BCR-ABL gene fusion, as some treatments are likely to be more effective.

Co-Editors-in-Chief

Charles M. Balch, MD, FACS

Charles M. Balch, MD, FACS Michael A. Caligiuri, MD

Michael A. Caligiuri, MD David S. Snyder, MD

David S. Snyder, MDOther chromosomes may begin to mutate in the accelerated and blast phases. Almost all people with CML will have the BCR-ABL gene detected in their blood or bone marrow.

Leukemia 101

Cancer can develop in almost any part of the body, including the blood. Cells typically divide in an orderly fashion. When they are worn out or damaged, they die, and new cells replace them. Cancer develops when genes begin to change, or mutate, within the structure of normal cells. These cells – now called cancer cells – grow against normal cells. Sometimes they form tumors; other times, they don’t. Tumors can be benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

Cancer can metastasize (spread) to other organs, tissues, bones or blood, but it is diagnosed according to where it begins in the body. If cancer starts in the blood, it is known as a hematologic (blood) cancer. If it spreads to the brain, however, it is still considered blood cancer and is treated as such. It does not become brain cancer.

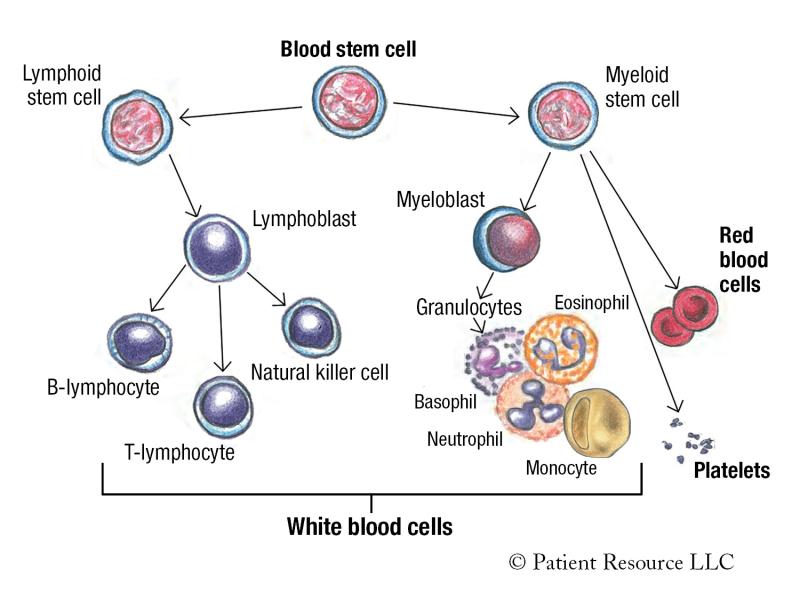

Leukemia is a type of blood cancer. Blood cells are made in the bone marrow, the soft, spongy center of some bones. They begin as immature blood stem cells that become either a myeloid stem cell or a lymphoid stem cell (see Figure 1).

Myeloid stem cells can mature into red blood cells, platelets and myeloblasts, which mature into granulocytes, a type of immune cell that has granules (small particles) with enzymes that are released during infections, allergic reactions and asthma. Granulocytes are a type of white blood cell involved in the immune system, and include basophils, eosinophils and neutrophils.

Lymphoid stem cells mature into lymphoblasts, which become B-lymphocytes, T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells. These white blood cells are also a part of the immune system.

Normal white blood cells help the body fight infections, and when they become old or damaged, they die and are replaced by new, healthy cells. However, in leukemia, the leukemic cells cannot fight infections properly and do not die when they should.

Large numbers of the leukemic cells accumulate in the bone marrow and/or the blood, which may slow down or prevent normal body functions, including the bone marrow’s normal production of healthy blood cells.

Leukemia is categorized by how fast the disease progresses and by the type of white blood cell it affects. “Acute” means it grows quickly; “chronic” means it grows slowly.

There are four major types of leukemia: acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

In acute leukemia, the leukemia cells look similar to immature white blood cells. The number of immature cells increases rapidly, preventing the bone marrow from making normal blood cells. Treatment should begin as soon as possible once a leukemia expert physician has been consulted because these fast-growing cells can quickly become life-threatening.

In chronic leukemia, the leukemia cells look similar to healthy, mature white blood cells, but the cells are unable to mature fully. The leukemia cells grow slowly and at different rates. Like acute leukemias, chronic leukemias are also classified as lymphocytic or myelogenous (myeloid) based on the type of cells in the bone marrow that become abnormal.

Lymphocytic leukemia begins in cells that become lymphocytes. Lymphocytic leukemias are also sometimes called lymphoid or lymphoblastic leukemias.

Myeloid leukemia begins in early myeloid cells, which become white blood cells (except for lymphocytes), red blood cells or cells that make platelets. Myeloid leukemias are sometimes called myelogenous, myelocytic or myeloblastic leukemias.

Figure 1. Blood Cell Development

Diagnosing CML

Your doctor will use a variety of tests to look for leukemic cells, chromosome abnormalities (which may indicate the Philadelphia chromosome), molecular markers and an enlarged spleen.

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential measures the number of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets in the blood, including the different types of white blood cells (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, basophils and eosinophils). Hemoglobin (the substance in the blood that carries oxygen) and hematocrit (the amount of whole blood that is made up of red blood cells) are also measured.

Blood chemistry study tests a sample of blood to measure the amount of certain substances in the body, including electrolytes (such as sodium, potassium and chloride), fats, proteins, glucose (sugar) and enzymes. Blood chemistry studies give important information about how well the kidneys, liver and other organs are working.

Flow cytometry measures the number of cells, the percentage of live cells and certain characteristics of cells, such as size and shape, in a sample of blood, bone marrow or other tissue.

A hepatitis panel looks for Hepatitis B, which can occur with CML.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are two procedures that often are done at the same time. A bone marrow aspiration uses a needle to remove a sample of fluid containing bone marrow. A bone marrow biopsy removes a sample of bone and bone marrow. Both the bone marrow and bone samples are sent to a laboratory to be examined under a microscope.

Molecular tests may be used to diagnose CML. Molecular testing is the process of identifying a disease by studying molecules, such as proteins, DNA and RNA, in tissues or fluids. With suspected CML, very sensitive tests may be used:

- Polymerase chain reaction may be used to detect the BCR-ABL fusion gene.

- Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) test may be used to look for activation of certain genes, which can help diagnose a disease, such as CML.

- Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) may be done at initial diagnosis to look for the presence of the BCR-ABL1 gene on the Philadelphia chromosome. This test may be repeated at specific intervals using a blood sample after treatment begins to monitor treatment effectiveness.

Cytogenetic analysis is used to look for changes in chromosomes, including broken, missing, rearranged or extra chromosomes in a sample of blood or bone marrow. It involves testing samples of tissue, blood or bone marrow, and it may be used to help diagnose a disease or condition, plan treatment or find out how well treatment is working. With CML, this test may be used to look for the Philadelphia chromosome.

Types of cytogenetic tests include the following:

- Karyotyping looks at a limited sample of bone marrow cells that are stimulated to divide in a culture dish.

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) looks at genes or chromosomes in cells and tissues. It is used to identify where a specific gene is located on a chromosome, how many copies of the gene are present and any chromosome abnormalities.

Computed tomography (CT) uses a computer linked to an X-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The pictures are taken from different angles and are used to create three-dimensional (3-D) views of tissues and organs. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the tissues and organs show up more clearly.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses radio waves and a powerful magnet linked to a computer to create detailed pictures of areas inside the body. These pictures can show the difference between normal and diseased tissue. MRI is especially useful for looking at the brain and the spine.

Ultrasound uses high-energy sound waves to look at tissues and organs inside the body. The sound waves make echoes that form pictures of the tissues and organs on a computer screen (sonogram).

Diagnosing CML

Diagnostic test results are typically used to determine the type or subtype of cancer. Solid tumors are usually staged based on the size of the tumor, whether lymph nodes contain cancer and whether the cancer has spread from the original site to other parts of the body. Because leukemias often do not form solid tumors, doctors use alternative methods to classify them.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system is used to classify CML into chronic phase, accelerated phase and blast crisis phase (see Table 1). This helps doctors determine the best disease management plan and prognosis (predicted outcome after treatment). The phases primarily describe the differences in the number of immature white blood cells, which are also known as myeloblasts or blasts. Other blood cell count levels and chromosome changes are also considered.

The progression of CML in the chronic phase is generally slow, and it may be several months or years before the next phase is reached (see Table 2). Response to treatment is typically better when treatment begins in this phase. The most advanced and aggressive phase is the blast crisis phase.

It is normal for bone marrow to contain 5 percent blasts. In a person who is diagnosed with CML, the blasts are usually higher than 5 percent. The higher the percentage of blasts, the more advanced the CML.

Most people with CML will have the Philadelphia chromosome but other chromosomes may begin to mutate in the accelerated and blast phases. Almost all people with CML will have the BCR-ABL gene detected in their blood or bone marrow.

| Phase | Description |

| Chronic Phase | Immature (blast) cells make up less than 10% of the cells in bone marrow or blood. |

| Accelerated Phase |

This phase is determined by any of the following features:

|

| Blast crisis phase |

|

Table 2 - Three Phases of CML

| Phase | Key Indicators | Symptoms | Progression |

|

Chronic (CP-CML) |

Increased number of white blood cells

|

None to a few

|

Very slow

(months to years) |

|

Accelerated (AP-CML) |

|

|

Four to six months

|

|

Blast or Blast Crisis (BP-CML) |

|

Fatigue, fever, poor appetite, weight loss, enlarged spleen

|

Without treatment, this phase will develop in about 3 to 4 years after diagnosis.

|

GETTING A SECOND OPINION

You may feel overwhelmed with the new information surrounding your CML diagnosis. To help ensure you understand the diagnosis and the suggested disease management plan, consider seeking a second opinion.

This involves asking another cancer specialist or group of specialists to review your medical records and confirm your doctor’s diagnosis and recommended plan. Other specialists can confirm your diagnosis and might suggest changes or alternatives to the proposed treatment. They can also answer any additional questions you may have.

Getting a second opinion does not mean you question your doctor. It simply gives you more information. Doctors in each oncology specialty bring different training and perspectives to cancer treatment planning. Another doctor’s opinion may change the diagnosis or reveal a treatment your first doctor was not aware of. You need to hear recommendations and reasoning for all your treatment options. A second opinion is also a way to ensure your pathology diagnosis and classification are accurate and to make you aware of potential clinical trials.

Key Takeaways

- Chronic myeloid leukemia is a cancer of the white blood cells.

- The majority of people diagnosed with CML have the Philadelphia chromosome.

- Classification helps your doctor recommend treatment based on the details of your CML.

The Philadelphia Chromosome

People with CML often have a mutation in their bone marrow called the Philadelphia chromosome, so it’s helpful to understand what this means. Every cell has a nucleus, which is a structure inside a cell that contains

46 chromosomes — 23 from your mother and 23 from your father. Each chromosome is made of DNA. Sections of DNA are known as genes, which contain the information to create a specific protein. The body needs proteins to function properly. If mutations (changes) occur in a gene, the protein it creates may not be able to perform its intended function. Or, it may create a new protein that normally doesn’t exist in the body.

Chromosomes contain specific genes. For example, chromosome 9 contains the ABL gene and chromosome 22 contains the BCR gene. In people with CML, the ABL gene on chromosome 9 breaks off and switches with a piece of chromosome 22 to form an abnormal chromosome 22 that contains the BCR-ABL1 gene. The abnormal chromosome created from the switching of the BCR and ABL1 genes is named the Philadelphia chromosome.

This type of mutation is known as a translocation because parts of the chromosomes break off and fuse together to form a new abnormal gene, which is also known as a fusion gene. This mutation is not inherited (passed from parent to child), and this fusion gene is not present in normal blood cells. It occurs during cell division when all the DNA is duplicated into a new cell.

Understanding Blood and Bone Marrow

Following are some of the components and functions of blood and bone marrow.

Blood is composed of red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (granulocytes, monocytes and lymphocytes), platelets and other substances suspended in fluid called plasma.

Blood stem cells are immature cells that can develop into all types of blood cells, including white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets. They may also be called hematopoietic (pronounced hee-MA-toh-poy-EH-tik) stem cells.

Bone marrow is the soft, spongy center of some bones, where blood is created.

Granulocyte is a type of immune cell that has granules (small particles) with enzymes that are released during infections, allergic reactions and asthma. Neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils are granulocytes, which are a type of white blood cell.

Hematopoietic stem cell is an immature cell that can develop into all types of blood cells, including white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets. Hematopoietic stem cells are found in the peripheral blood and the bone marrow.

Lymphoid refers to lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell.

Myeloblast is a type of immature white blood cell that forms in the bone marrow. Myeloblasts become mature white blood cells called granulocytes, which include neutrophils, basophils and eosinophils.

Myeloid refers to bone marrow and may also describe certain types of hematopoietic (blood-forming) cells found in the bone marrow. Myeloid is sometimes used as a synonym for myelogenous.

Plasma is the liquid component of blood that carries water, nutrients, hormones, proteins and enzymes to many parts of the body.

Plasma cells produce antibodies to help fight germs and viruses and to stop infection and disease. They are primarily found in the bone marrow.

Platelets are blood cells that gather around wounds to form clots and stop bleeding. They also play a part in repairing wounds and creating new blood vessels.

Red blood cells carry oxygen from the lungs to other parts of the body.

White blood cells help the body fight infection.

Questions to Ask your Doctor

- What phase of CML do I have?

- What does my CML phase mean for my outlook?

- Do I have the Philadelphia chromosome?