Melanoma

Treatment Planning

The landscape of treating melanoma has changed dramatically in the past 10 years. Research and clinical trials have led to more effective treatment options, offering patients more hope. People are surviving longer after a melanoma diagnosis and enjoying a higher quality of life.

Understanding the options available to treat your melanoma is essential. Working closely with your medical team to learn about your choices while having honest conversations about each option and the potential side effects will help you feel more comfortable with the treatment decisions you make.

Treatment Basics

Treatment for melanoma focuses on whether the treatment is local (confined to one area) or systemic (which travels somewhere else in the body), whether it’s given by injection, infusion or orally as a pill, whether it’s given before or after surgery and the order in which it is given.

- Local treatments target specific areas of the body and include surgery and occasionally radiation therapy. Some treatments involve injecting the drug directly into the lesion or topical application to the skin close to a melanoma.

- Systemic treatments, including drug therapies such as targeted therapy, immunotherapy and chemotherapy, travel through the bloodstream. They can help destroy melanoma cells that may be hiding in other places, such as the liver, lungs or bones. These hidden cancer cells are usually too small to detect with laboratory testing or imaging studies.

- Oral treatment is given in pill form.

- Neoadjuvant treatment is given before surgery to shrink a tumor so it can be more easily or safely removed with surgery.

- Adjuvant treatment is given after primary treatment, which is usually surgery.

- First-line therapy is the first treatment given.

- Second-line therapy is given when the first-line therapy doesn’t work, is no longer effective or has side effects that are not well tolerated.

Most people will receive more than one type of treatment. Following are descriptions of some common types of treatment.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Surgery

Surgery is usually the first treatment used for early stage local and regional melanomas and is also used for some metastatic melanomas. Often, surgery is the only treatment needed. The two main types of surgery for melanoma include the following:

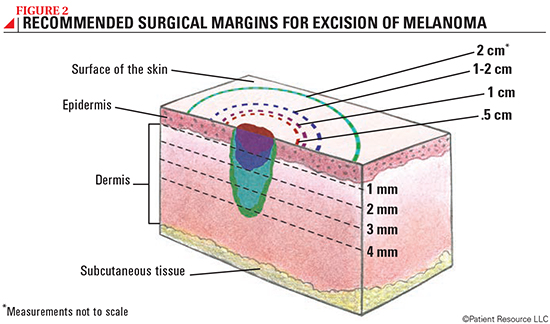

- A wide excision is used to remove the melanoma and an additional portion of normal-looking tissue, which is called a surgical margin (see Figure 1). The thicker the melanoma is, the larger the surgical margin needed. The tissue removed from the margin will be carefully examined by a pathologist under a microscope to determine whether any cancer cells remain. More surgery may be needed if the margins contain cancer cells.

- A lymph node dissection is a type of surgery that is sometimes performed to remove lymph nodes in the region after a biopsy if pathology results show a melanoma spread (metastasis) in the sentinel lymph node (see Understanding Your Diagnosis, page 6). At the end of the procedure, the surgeon will likely place drains into the area to collect any blood or fluid from the region where the lymph nodes were removed. The incision will then be closed, and the wound will be covered by a dressing. Your health care team will give you information for incision and drain care, if applicable.

Drug Therapy

Drugs are a type of systemic therapy used to destroy cancer cells, prevent progression or slow the cancer’s growth. Drug therapy may be given intravenously (IV) through a vein, subcutaneously into the skin, or orally, and it may be used alone or in combination with other drug therapies or other treatment options.

Most drug therapies are approved for unresectable (inoperable) and metastatic melanoma, which has spread to other organs. However, progress has been made with treating earlier stages of melanoma as well such as Stages II and III. Drug therapies are approved as first-line and second-line therapy. When and which drug therapy is used depends on the stage of the melanoma, the risk of recurrence, whether there was previous treatment and whether there was neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment. Immunotherapy and targeted therapies may now be used as second-line therapy for Stages II and III.

The drug therapies used to treat melanoma are the following.

Targeted therapy uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific types of cancer cells. Unlike chemotherapy, which attacks healthy cells as well as cancer cells, targeted therapy is designed to affect only cancer cells. Targeted therapy drugs approved for melanoma are known as signal transduction inhibitors, which block signals passed between one molecule and another. Blocking the signals can kill some cancers. Targeted therapy drugs may be given alone or in combination with other drug therapies. Taken orally, targeted therapies may be used to treat both Stage III and Stage IV melanomas that are inoperable or metastatic.

Several mutations (abnormalities) in genes and proteins have been found in melanoma for which targeted therapies have been approved. A mutation in the BRAF gene has been found in many patients with melanoma. This mutation can cause melanoma cells to produce proteins that help cancer cells to grow. A type of targeted therapy known as a BRAF inhibitor can be used as part of a regimen to treat melanomas with this mutation. BRAF inhibitors attack the BRAF protein directly and can shrink or slow the growth of tumors in melanoma that has spread or can’t be completely removed.

Another target is the MEK protein. Drugs that block MEK proteins are called MEK inhibitors and can also be used as part of a regimen to treat melanomas with BRAF mutations.

For patients with a BRAF mutation, doctors could prescribe a combination of a BRAF and MEK inhibitor.

Another mutation found in some melanomas is the NTRK gene. The treatment approved for this mutation is considered tumor-agnostic because it is approved to treat the NTRK fusion regardless of the type of cancer or where it is in the body.

In some rare melanomas, a mutation in the KIT gene has been found and these can be treated with KIT inhibitors.

Immunotherapy helps the body’s own immune system recognize and destroy cancer cells. By training the immune system to respond to cancer, this strategy has the potential for a response that can extend beyond the end of treatment. Most are given intravenously (IV), but some may be used as local treatment that is topical. Immunotherapy can be given as the primary treatment, also known as first-line therapy, for melanomas that cannot be removed surgically or that are metastatic. Some immunotherapy drugs may be combined and used as second-line treatment for patients who have not responded well to initial immunotherapy.

Immunotherapies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as cytokines, immunomodulators, oncolytic viruses, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy and a bispecific T-cell engager.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are antibodies made in a laboratory that target specific tumor antigens found on cancer cells. Some mAbs mark cancer cells so that the immune system will better recognize and destroy them. Other mAbs bring T-cells, a type of white blood cell, close to cancer cells, helping the immune cells kill the cancer cells. They can also carry cancer drugs, radiation particles or laboratory-made cytokines (proteins that enable cells to send messages to each other) directly to cancer cells.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a type of mAb that helps the immune system better recognize that melanoma cells are foreign to the body, which allows the immune cells to better destroy the cancer (see Figure 3). The immune checkpoint inhibitors are monoclonal antibodies that block the receptors of PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1), PD-L1 (programmed cell death-ligand 1) and CTLA-4 (cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen 4), and thereby inhibit their activating signal to the cell. They may be given intravenously or by subcutaneous injection.

Cytokines are substances secreted by certain cells of the immune system that boost the whole immune system. They can be used alone or in combination with other treatments to produce increased and longer-lasting immune responses. Cytokines aid in immune cell communication and play a big role in the full activation of an immune response. This approach works by introducing large amounts of laboratory-made cytokines to the immune system to promote nonspecific immune responses as a systemic therapy.

Interleukins help control the activation of certain immune cells to better destroy the cancer.

Oncolytic virus immunotherapy uses viruses that directly infect tumor cells to cause an immune response. It is typically given as a local treatment by injection directly into the tumor.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy is in a class of immunotherapy known as adoptive cellular therapy. It uses a patient’s own lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) as treatment for cancer. Some lymphocytes can recognize a tumor as abnormal and penetrate it. TIL therapy removes these specific lymphocytes from a patient’s tumor. They are multiplied in a lab and given back to the patient to help kill cancer cells. It is approved as second-line therapy for melanoma that can’t be removed by surgery or metastatic melanoma that was previously treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

A bispecific T-cell engager was recently approved for inoperable or metastatic uveal melanoma. It targets the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and attaches to a T-cell, which is part of your immune system. This treatment helps the immune system better find and kill cancer cells.

Chemotherapy uses powerful drugs to kill rapidly multiplying cells throughout the body. It is rarely used alone. When used, it is typically part of a combination of other drug therapies or if all other drug therapies have failed. A new chemotherapy has been approved for uveal melanoma that has spread to the liver.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy radiation to destroy cancer cells and shrink tumors. Though radiation therapy is not typically used to treat the original melanoma, it may be given to areas where lymph nodes were surgically removed or after surgery to remove the melanoma if the risk of recurrence is considered to be high.

It may also be given to relieve symptoms related to the spread of melanoma, particularly to the bones or brain. When given to the brain, whole-brain radiation therapy or localized stereotactic radiation therapy may be used. Stereotactic radiation is given to a specific area of the body in a high dose.

Types of radiation used include external-beam radiation therapy, which uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, image-guided radiation therapy and stereotactic radiosurgery or stereotactic radiotherapy.

Clinical Trials

The advances in treating melanoma are due to clinical trials. New therapies are continually being researched and clinical trials need volunteers. Ask your doctor if you should consider this option as a first-line treatment or at any other time during your treatment.

Understanding Resistance

Recent advances in therapies have been game-changers in treating melanoma. However, it is known that cancer can become resistant to these therapies. This means the disease may stop responding after treatment has been underway for a length of time.

Resistance is believed to develop when some cancer cells survive after being treated. The surviving cells recover and begin to grow and divide again, often with new genetic changes that the initial treatment is not designed to target. Research is underway to understand how and why resistance develops and to find ways to prevent it or slow it down to extend the effectiveness of the original therapy.

If resistance has occurred, new tests may be performed to determine whether new genetic alterations have developed. If they have, a different drug may be available to treat it. Talk with your doctor about the possibility of developing resistance to any immunotherapies or targeted therapies you may take.

Recurrence or Secondary Melanoma

Despite successful treatment, melanoma can return months or years later. Known as a recurrence, melanoma can return to the same area as the original melanoma, in surrounding skin or tissues, in lymph nodes or at other sites in the body (known as distant recurrence).

Once you’ve had melanoma, you are at risk of having a second melanoma. A new melanoma can appear anywhere on your body not related to the original melanoma. Keeping follow-up appointments and doing skin exams are important for detecting a recurrence early so that treatment may begin as soon as possible.

Stay on Time Taking Your Medication

Some melanoma patients have the option of taking targeted therapy medications in the comfort of their home. These therapies are typically oral medications that you are responsible for taking on time, every time, also known as medication adherence. Correctly taking your medication is important because it can influence the effectiveness of the therapy and the management of side effects.

If your medications are not taken exactly as prescribed, the consequences can lead to unnecessary or unrelieved side effects, physician visits, hospitalizations and even cancer progression. Talk with your doctor before treatment begins about how and when to take your medication. It can be challenging to remember to take your medications, especially if you feel overwhelmed or confused by your treatment plan. Don’t be afraid to ask for help managing your treatment at home.

Words to Know

Some of the treatment terms your medical team uses may be confusing. These explanations may help you feel more informed as you make the important decisions ahead.

First-line therapy is the first treatment used.

Second-line therapy is given when the first-line therapy does not work or is no longer effective.

Standard of care refers to the widely recommended treatments known for the type and stage of cancer you have.

Neoadjuvant therapy is given to shrink a tumor before the primary treatment (usually surgery).

Adjuvant therapy is additional cancer treatment given after the primary treatment (usually surgery or radiotherapy) to destroy remaining cancer cells and lower the risk that the cancer will come back.

Local treatments are directed to a specific organ or limited area of the body and include surgery and radiation therapy.

Systemic treatments travel throughout the body and are typically drug therapies, such as gene therapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

In situ refers to the cancer’s original place. For example, with carcinoma in situ (stage 0 cancer), abnormal cells are found only in the place where they first formed. They have not spread.

Progression means the cancer is growing or spreading without going away after treatment.

Progression-free survival is the length of time during and after the treatment of cancer that a patient lives with the disease, but without worsening.

Partial response means the cancer responded to treatment but is still present.

Complete response is the disappearance of all signs of cancer in response to treatment. This does not always mean the cancer has been cured.

Nodal recurrence happens when the melanoma returns in lymph nodes.

Overall survival is the amount of time a patient survives after their diagnosis or the start of treatment.

| Common Drug Therapies for Melanoma |

| Chemotherapy |

| dacarbazine (DTIC-Dome) |

| HEPZATO KIT (melphalan for Injection/Hepatic Delivery System) containing melphalan |

| Immunotherapy |

| interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Aldesleukin, Proleukin) |

| ipilimumab (Yervoy) |

| lifileucel (Amtagvi) |

| nivolumab (Opdivo) |

| nivolumab and relatlimab-rmbw (Opdualag) |

| peginterferon alfa-2b (Sylatron) |

| pembrolizumab (Keytruda) |

| talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic/T-VEC) |

| tebentafusp-tebn (Kimmtrak) |

| Targeted Therapy |

| dabrafenib (Tafinlar) |

| larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) |

| trametinib (Mekinist) |

| vemurafenib (Zelboraf) |

| Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) Therapy |

| lifileucel (Amtagvi) |

| Some Possible Combinations |

| atezolizumab and hyaluronidase-tqjs (Tecentriq) with cobimetinib (Cotellic) and vemurafenib (Zelboraf) |

| atezolizumab (Tecentriq) with cobimetinib (Cotellic) and vemurafenib (Zelboraf) |

| binimetinib (Mektovi) and encorafenib (Braftovi) |

| cobimetinib (Cotellic) and vemurafenib (Zelboraf) |

| dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and trametinib (Mekinist) |

| ipilimumab (Yervoy) and nivolumab (Opdivo) |