Lung Cancer

Treatment Planning

Research and clinical trials have led to more treatment options for lung cancer in the past 10 years, offering hope to people with cancer and their loved ones. This ongoing research holds the promise of more treatment options in the future as well as potentially finding a cure. If possible, find a doctor who specializes in your type of lung cancer and who is knowledgeable about the latest treatment advances and potential clinical trials.

Once all diagnostic test results are in (including molecular testing), your doctor will make a diagnosis, determine a stage and use that information to develop a treatment plan for you based on whether you have non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or small cell lung cancer (SCLC). People with NSCLC (except

those at Stage I) should have molecular testing because drug therapy will likely be used in addition to surgery or radiation. This will be done either before (neoadjuvant) or after (adjuvant), or before and after the surgery.

Treatment Options

Your treatment plan may include one or more of the following.

Surgery, also called resection, is typically the primary treatment for early-stage (Stages I, II and some IIIA) NSCLC tumors. It is not commonly used for SCLC and is typically reserved only for very early-stage SCLC disease. In this case, chemotherapy is administered after surgery. In some cases of brain metastases, surgery may be used.

A board-certified thoracic surgeon who is experienced in lung cancer should determine whether the tumor(s) can be successfully removed. The procedure selected will depend on how much of your lung is affected, tumor size and location and your overall health.

The following types of resection may be done by open thoracotomy (a large incision in the chest wall that requires separation of the ribs) or by less invasive procedures, such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) with or without robotic surgery. These are performed as the doctor inserts scopes

through small incisions. These VATS procedures may help preserve muscles and nerves, reduce complications and shorten recovery time. Open surgery options include:

- Wedge resection removes the tumor with a triangular piece of a lobe of the lung.

- Segmental resection (segmentectomy) removes a larger section of a lobe.

- Lobectomy removes one of the lungs’ five lobes.

- Pneumonectomy removes an entire lung.

- Sleeve resection (sleeve lobectomy) removes part of the bronchus (main airway) or pulmonary artery to the lung along with one lobe to save other portions of the lung.

Some early-stage tumors may be removed with robotic surgery. Special equipment provides

a three-dimensional view inside the body while the surgeon guides a robotic arm and high-precision tools that can bend and rotate much more than the human wrist. Neurosurgery may be an option for treating brain metastases. Finding a surgeon with extensive training and experience is highly

recommended.

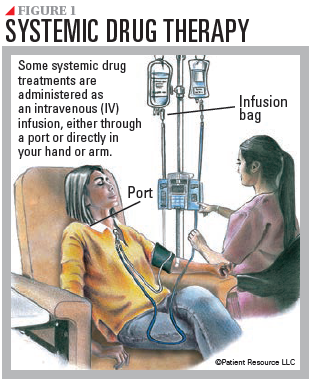

Drug therapy is systemic treatment that travels throughout the body (see Figure 1).

Chemotherapy is typically part of the treatment plan for most stages of NSCLC and is the primary treatment for all stages of SCLC. It may be given alone or in combination with surgery, radiation therapy or immunotherapy.

In early stage NSCLC, it may be used before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy) to help shrink the tumor, after surgery (adjuvant therapy) to kill remaining cells, as maintenance therapy following standard chemotherapy to prevent recurrence, or as palliative care to help relieve symptoms. For some people with Stage III, a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy may be used and followed by immunotherapy. For metastatic NSCLC, chemotherapy may be combined with immunotherapy (chemoimmunotherapy) or targeted therapy.

For limited-stage SCLC, chemotherapy is combined with radiation therapy to the chest. In extensive-stage SCLC, chemotherapy is combined with immunotherapy. Chemotherapy is also used for second-line treatment. If a recurrence occurs, depending on how quickly the cancer returns, the first chemotherapy

combination may be used again in the second-line setting if there was a good and long lasting response to therapy. If there was not, other chemotherapies are approved to treat SCLC as second-line therapy, or a different combination of chemotherapies may be used.

Immunotherapy uses drugs to stimulate your immune system to find and attack cancer. It may be used alone or in combination with other types of immunotherapy or chemotherapy. It is standard first-line therapy for Stage IV NSCLC without specific molecular alterations and is approved in combination with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy for early stage NSCLC. It is standard after chemotherapy and radiotherapy for unresectable Stage III NSCLC and standard with chemotherapy (chemoimmunotherapy) for extensive-stage SCLC. Its use with chemoradiation as initial therapy in limited-stage SCLC is being explored. Immunotherapies that are PD-L1 antibodies are now indicated in addition to chemotherapy and radiation therapy for limited-stage as well as extensive stage SCLC. A new type of immunotherapy was recently approved for extensive-stage SCLC with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy.

Many of the immunotherapies approved for lung cancer are immune checkpoint inhibitors, which are monoclonal antibody drugs given intravenously that prevent the immune system from slowing down, allowing it to keep up its fight against the cancer. Checkpoints keep the immune system “in check,” preventing an attack on normal cells. They are like the “brakes” of the immune system. Checkpoint inhibitors take the “brakes” off the immune system.

Three checkpoint receptors are available to slow down the immune system:

- PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1) is a receptor found on T-cells (a type of immune cell) that helps keep the immune system in check. PD-1 can tell the immune system to slow down only if it connects with PD-L1.

- PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) is a protein that, when combined with PD-1, sends a signal to reduce the production of T-cells and enable more T-cells to die. When PD-1 (the receptor) and PD-L1 (the protein) combine, the reaction signals that it is time to slow down.

- CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4) is another checkpoint like PD-1. CTLA-4, however, can connect with more than one protein.

The goal of immune checkpoint inhibitors is to prevent PD-1 and PD-L1 from connecting so that the immune system does not slow down. Immunotherapy is given through an IV and prevents these connections by targeting and blocking PD-1, PD-L1 or CTLA-4. This treatment allows the immune cells to continue fighting the cancer.

Depending on your diagnosis, your doctor may test for the tumor’s PD-L1 expression, which may indicate the tumor could respond to immunotherapy. Tumors that have a high level are considered good candidates for treatment with immunotherapy.

A bispecific T-cell engager, which is a type of immunotherapy, was recently approved for SCLC that targets the protein DLL3, which is commonly found on SCLC cells. Because DLL3 is so prevalent in SCLC, biomarker testing is not required to receive this new drug.

Chemoimmunotherapy combines chemotherapy with immunotherapy. It may be used to treat early stage NSCLC before or after surgery or both. It may be used in Stage IV NSCLC if there are no molecular drivers (biomarkers) and if the PD-L1 score is less than 50.

This therapy is currently the preferred first-line treatment option for the majority of patients with advanced NSCLC without driver genetic alterations and is the preferred treatment for extensive-stage SCLC.

Molecular therapy is personalized treatment that may be used if the tumor contains a known biomarker. Most of these therapies are given orally as a pill and are recommended as first-line therapy for NSCLC. If the first-line therapy is not effective, another one may be considered. Unlike chemotherapy, which attacks healthy cells as well as cancer cells, it is designed to affect only cancer cells. Currently, there are no approved molecular therapies for SCLC.

To determine whether you are a candidate for molecular therapy, a biopsy tissue sample and blood sample must be tested at a specialized lab to detect any known molecular biomarkers. This should be done before your treatment begins. Ask your doctor whether tissue from a previous biopsy can be used, if applicable.

Because many tumors do not have biomarkers for which approved therapies currently exist, clinical trials are underway to find effective treatments for additional genetic abnormalities. If your tumor tested positive for a biomarker that does not have an approved targeted treatment, ask your doctor about participating in a clinical trial.

The genetic alterations treated by molecular therapy may include gene fusions, which are created by joining two different genes together, and mutations, which can occur when there is any change in the DNA sequence of a cell. They include the following:

- ALK fusions

- BRAF mutations

- EGFR mutations

- KRAS mutations

- MET exon 14 skipping mutations

- NTRK fusions

- RET fusions

- ROS1 fusions

Some drugs that treat these abnormalities are tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). In a healthy cell, tyrosine kinases are enzymes that are responsible for certain functions such as cell signaling (communication

between cells) and cell growth and division. These enzymes may be too active or found at high levels in some cancer cells. Blocking them may help keep cancer cells from growing.

TKIs are now available for EGFR mutations, ALK fusions, NTRK fusions, ROS1 fusions, MET exon 14 skipping mutations, RET fusions and certain BRAF mutations for first-line therapy. TKIs that target KRAS

mutations are available for second or later lines of therapy.

In NSCLC, molecular therapy is associated with higher response rates, longer-lasting benefits and far fewer side effects than chemotherapy.

Targeted therapy is systemic drug therapy directed at proteins involved in making cancer cells grow that do not have proven biomarkers. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and angiogenesis inhibitors, which are given intravenously (by IV) and always with chemotherapy, are the types of targeted therapy approved to treat NSCLC. An angiogenesis inhibitor is approved for certain SCLC diagnoses.

- Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are laboratory-made antibodies designed to target specific tumor antigens, which are substances that cause the body to make a specific immune response. They can work in different ways, such as flagging targeted cancer cells for destruction, blocking growth signals and receptors, and delivering other therapeutic agents directly to targeted cancer cells.

- Angiogenesis inhibitors shut down vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein that is essential for creating blood vessels. Solid tumors need a blood supply if they are going to grow beyond a few millimeters. But with no vessels to supply blood, the tumor eventually “starves” and dies. Angiogenesis inhibitors are often given in combination with chemotherapy.

An antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) is a type of monoclonal antibody (mAb) that is designed to target only cancer cells, leaving healthy cells alone. The mAb binds to specific proteins or receptors found on certain types of cells, including cancer cells. The linked chemotherapy drug enters these cells and kills them without harming other cells. An ADC has been approved to treat the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) mutation. Other ADCs are being investigated in clinical trials.

Radiation therapy, also called radiotherapy, uses high-energy radiation to destroy cancer cells and shrink tumors. It is often combined with other treatment types for NSCLC and SCLC. It may also be used as palliative care to help relieve pain from cancer that spreads to the bone.

External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most common form of radiation therapy used. EBRT comes in multiple forms:

- Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) uses precise mapping to shape and aim radiation beams at the tumor(s) from multiple directions, typically causing less damage to normal tissue.

- Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) is a form of 3D-CRT offering precision delivery of high-dose radiation through beams aimed at the tumor from multiple directions. SBRT may be the primary treatment for small tumors or early-stage cancers when a person cannot undergo surgery or makes the decision not to have surgery.

- Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is an advanced form of 3D-CRT that delivers radiation from a machine that moves around the person, aiming beams at varying strengths for increased precision. This technique may be used to treat tumors located near sensitive areas such as the spinal cord.

- Proton beam therapy destroys cancer cells by using charged particles called protons. This treatment typically results in less damage to healthy tissue and fewer side effects than traditional radiation therapy.

- Volumetric arc-based therapy (VMAT) delivers IMRT in an arc shape around the tumor(s).

For NSCLC, radiation therapy can be used after surgery to treat any remaining cancer. It may also be combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiation), be the primary therapy for Stage I and some Stage II tumors, treat where the tumor has spread, including the brain, or alleviate bone pain from metastases.

For SCLC, radiation therapy is used for limited-stage SCLC that has not spread to the lymph nodes and cannot be treated with surgery. It is often combined with chemotherapy in a treatment called chemoradiation. In some instances, your doctor may offer prophylactic cranial irradiation to prevent the spread of SCLC to the brain. Before moving forward, talk with your doctor about the potential advantages and risks of this preventive approach for your specific situation. People with extensive-stage SCLC may receive radiation therapy to treat remaining disease in the chest.

Chemoradiation, also called chemoradiotherapy or concurrent chemoradiation, combines chemotherapy with radiation therapy. It makes cancer cells more sensitive to radiation, making it easier for the radiation therapy to kill them. It is an option for some Stage IIB and Stage III NSCLCs. Patients with limited-stage SCLC are usually treated with both chemotherapy and radiation therapy given concurrently for two of four chemotherapy cycles.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) may be used to treat small NSCLC tumors when surgery is not an option. A needle placed directly into the tumor passes a high-frequency electrical current to the tumor that destroys cancer cells with intense heat. It is rarely used for SCLC tumors.

Cryosurgery, also called cryoablation and cryotherapy, kills cancer cells by freezing them with a probe or another instrument that is super-cooled with liquid nitrogen or similar substances. An endoscope, which is a thin tube-like instrument, is used for this procedure to treat NSCLC tumors in the airways of the lungs. It is not used to treat SCLC.

Photodynamic therapy kills cancer cells by injecting a drug that has not yet been exposed to light into a vein. The drug is drawn to cancer cells more than normal cells. Fiber optic tubes are then used to carry a laser light to the cancer cells, where the drug becomes active and kills the cells. It is used mainly to treat tumors on or just under the skin or in the lining of internal organs. When the tumor is in the airways, therapy is directed to the tumor through an endoscope. It may help relieve breathing problems or bleeding in NSCLC and can also treat small tumors. It is not used for SCLC.

Clinical trials may offer the opportunity to try an innovative treatment that is testing drug therapies or types of surgery or radiation therapy before they are widely available (see Clinical Trials). Some are even underway to find improved methods to stop smoking.

Consolidation therapy is treatment that is given after cancer partially responded to initial therapy. It is used to kill any cancer cells that may be left in the body. It may include radiation therapy, surgery or treatment with drug therapies designed to kill cancer cells.

Monitoring for Resistance

Despite an initial response to treatment, many lung cancer patients develop resistance to some forms of therapy, which decreases the response and success of treatment. The most well-known treatments that can develop resistance in lung cancer are molecular and targeted therapies. However, resistance can also happen with chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy.

Resistance is believed to develop when some cancer cells survive after being treated. The surviving cells recover and begin to grow and divide again, often with new genetic changes that the initial treatment is not designed to target. Research is underway to understand how and why resistance develops

and to find ways to prevent it or slow it down to extend the effectiveness of the original therapy.

Throughout treatment, patients will be monitored to watch for their treatment becoming less effective and to monitor for cancer progression. This may indicate that the cancer has developed resistance. For those with a genetic alteration whose cancer later progresses, they will need to be retested to determine whether there is a new actionable genetic alteration for which treatment is available.

Talk with your doctor about the possibility of developing resistance to treatment, specifically molecular and targeted therapies. For some cases of NSCLC, another drug therapy option may be available.

Keeping Follow-up Appointments

As you go through treatment, your doctor and health care team will also monitor your symptoms, side effects, possible metastases to the brain or other sites and health status. Regular follow-up appointments are crucial to your care. They offer you the opportunity to discuss any issues you are having with treatment, address new symptoms or concerns and manage ongoing treatment side effects. Tell your doctor how you feel physically, mentally and emotionally, or between appointments if something changes.

Your doctor also uses follow-up appointments to watch for resistance as well as a recurrence. In either case, your doctor may be able to change your treatment regimen.

Never hesitate to reach out, especially now that online portals are widely available.

| Common Drug Therapy for Lung Cancer |

| Chemotherapy |

| carboplatin (Paraplatin) |

| cisplatin (Platinol) |

| docetaxel (Docefrez, Taxotere) |

| doxorubicin (Adriamycin) |

| etoposide (Etopophos) |

| gemcitabine (Gemzar, Infugem) |

| irinotecan (Camptosar) |

| lurbinectedin (Zepzelca) |

| methotrexate |

| paclitaxel (Taxol) |

| paclitaxel protein-bound (Abraxane) |

| pemetrexed (Alimta) |

| topotecan (Hycamtin) |

| vinorelbine (Navelbine) |

| Immunotherapy |

|

Bispecific T-cell engager

|

| tarlatamab-dlle (Imdelltra) |

|

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

|

| atezolizumab (Tecentriq) |

| atezolizumab and hyaluronidase-tqjs (Tecentriq Hybreza) |

| cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo) |

| durvalumab (Imfinzi) |

| ipilimumab (Yervoy) |

| nivolumab (Opdivo) |

| pembrolizumab (Keytruda) |

| tremelimumab (Imjudo) |

| Molecular therapy |

|

ALK fusion

|

| alectinib (Alecensa) |

| brigatinib (Alunbrig) |

| ceritinib (Zykadia) |

| crizotinib (Xalkori) |

| ensartinib (Ensacove) |

| loratinib (Lorbrena) |

|

BRAF V600E mutation

|

| dabrafenib (Tafinlar)/trametinb (Mekinist) |

| encorafenib (Braftovi)/binimetinib (Mektovi) |

|

EGFR mutation

|

| afatinib (Gilotrif) |

| amivantamab-vmjw (Rybrevant) |

| dacomitinib (Vizimpro) |

| erlotinib (Tarceva) |

| gefitinib (Iressa) |

| lazertinib (Lazcluze) |

| mobocertinib (Exkivity) |

| osimertinib (Tagrisso) |

|

KRAS mutation

|

| adagrasib (Krazati) |

| sotorasib (Lumakras) |

|

MET exon 14 skipping mutation

|

| capmatinib (Tabrecta) |

| tepotinib (Tepmetko) |

|

NTRK gene fusion

|

| entrectinib (Rozlytrek) |

| larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) |

| repotrectinib (Augtyro) |

|

RET fusion

|

| pralsetinib (Gavreto) |

| selpercatinib (Retevmo) |

|

ROS1 fusion

|

| crizotinib (Xalkori) |

| entrectinib (Rozlytrek) |

| repotrectinib (Augtyro) |

| Targeted Therapy |

|

EGFR inhibitors

|

| necitumumab (Portrazza) |

|

HER2 mutations

|

| fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki (Enhertu) |

|

VEGF inhibitors (angiogenesis inhibitors)

|

| bevacizumab (Avastin) |

| bevacizumab-awwb (Mvasi) |

| ramucirumab (Cyramza) |

| Some Possible Combinations |

| amivantamab-vmjw (Rybrevant) with carboplatin (Paraplatin) and pemetrexed (Alimta) |

| atezolizumab (Tecentriq) with bevacizumab (Avastin) with carboplatin (Paraplatin) and paclitaxel (Taxol) |

| atezolizumab (Tecentriq) with carboplatin (Paraplatin)and etoposide (Etopophos) |

| atezolizumab (Tecentriq) with paclitaxel protein-bound (Abraxane) and carboplatin (Paraplatin) |

| bevacizumab (Avastin) with carboplatin (Paraplatin) and paclitaxel (Taxol) |

| bevacizumab-awwb (Mvasi) with carboplatin (Paraplatin) and paclitaxel (Taxol) |

| bevacizumab-bvzr (Zirabev) with carboplatin (Paraplatin) and paclitaxel (Taxol) |

| cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo) in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy |

| docetaxel (Taxotere) with cisplatin (Platinol) |

| docetaxel injection with cisplatin (Platinol) |

| durvalumab (Imfinzi) with etoposide (Etopophos) and either carboplatin (Paraplatin) or cisplatin (Platinol) |

| durvalumab (Imfinzi) with tremelimumab (Imjudo) and platinum chemotherapy |

| etoposide (Etopophos) with cisplatin (Platinol) |

| gemcitabine (Gemzar, Infugem) and cisplatin (Platinol) |

| ipilimumab (Yervoy) with nivolumab (Opdivo) |

| lazertinib (Lazcluze) with amivantamab-vmjw (Rybrevant) |

| necitumumab (Portrazza) with gemcitabine (Gemzar) and cisplatin (Platinol) |

| nivolumab (Opdivo) plus platinum-doublet chemotherapy |

| nivolumab (Opdivo) with ipilimumab (Yervoy) |

| nivolumab (Opdivo) with ipilimumab (Yervoy) and two cycles of platinum doublet chemotherapy |

| paclitaxel protein-bound (Abraxane) with carboplatin (Paraplatin) |

| paclitaxel (Taxol) with cisplatin (Platinol) |

| pembrolizumab (Keytruda) with carboplatin (Paraplatin) and either paclitaxel (Taxol) or paclitaxel protein-bound (Abraxane) |

| pembrolizumab (Keytruda) with pemetrexed (Alimta) and platinum chemotherapy |

| pemetrexed (Alimta) with cisplatin (Platinol) |

| pemetrexed (Alimta) with pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and platinum chemotherapy |

| ramucirumab (Cyramza) with docetaxel (Taxotere) |

| ramucirumab (Cyramza) with erlotinib (Tarceva) |

| tremelimumab (Imjudo) with durvalumab (Imfinzi) and platinum-based chemotherapy |

| vinorelbine (Navelbine) with cisplatin (Platinol) |

As of 12/30/24

Taking your medication as directed is crucial for success

Some lung cancer patients now have the option of taking molecular and targeted therapy medications in the comfort of their home. These new therapies are typically oral medications that you are responsible for taking on time, every time, also known as medication adherence. Correctly taking your medication is important because it can influence the effectiveness of the therapy and the management of side effects.

Most cancer therapies are designed to maintain a specific level of drugs in your system for a certain time based on your cancer type and stage, your overall health, previous therapies and other factors. If your medications are not taken exactly as prescribed, the consequences can lead to unnecessary or unrelieved side effects, physician visits, hospitalizations and even cancer progression. To be fully effective, every treatment dose must be taken with the same kind of accuracy, precise timing and safety precautions, for as long as prescribed.

Talk with your doctor before treatment begins about how and when to take your medication. It can be challenging to remember to take your medications, especially if you feel overwhelmed or confused by your treatment plan. Don’t be afraid to ask for help managing your treatment at home.

Download the Patient Resource Medication Journal to keep track of your medications at PatientResource.com/Medication_Journal

Commonly used terms

You will hear a lot of new information as you learn about your treatment options. Some of the terms your medical team uses may be confusing. These explanations may help you feel more informed as you make the important decisions ahead.

First-line therapy is the first treatment used.

Second-line therapy is given when the first-line therapy does not work or is no longer effective.

Standard of care refers to the widely recommended treatments known for the type and stage of cancer you have.

Neoadjuvant therapy is given to shrink a tumor before the primary treatment (usually surgery).

Adjuvant therapy is additional cancer treatment given after the primary treatment (usually surgery or radiotherapy) to destroy remaining cancer cells and lower the risk that the cancer will come back.

Local treatments are directed to a specific organ or limited area of the body and include surgery and radiation therapy.

Systemic treatments travel throughout the body and are typically drug therapies, such as chemotherapy, molecular therapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

Response to therapy means that the cancer has reduced in size or lost its blood supply in a manner that can be measured by CT or MRI.