Cervical Cancer

Treatment Options

Developing a treatment plan requires you and your health care team to evaluate many things, such as the size of the tumor, the stage, your age and overall health, and your expectations for fertility in the future. If you are pregnant when the cancer is found, your doctor will consider how far along you are and may recommend delaying treatment until after you give birth. Once all these factors are considered, your doctor will discuss the types of treatment that are available to you.

Cervical cancer is often treated with more than one mode of therapy. Your treatment plan should explain the goals and the expected length of each, along with possible side effects. You may also consider getting a second opinion.

Before making any decisions, if possible, talk with your doctor about how each option may affect your fertility. Depending on where you are in your life, this may be a challenging topic. You may be in the process of trying to become pregnant, or you may be years away from even thinking about it. Regardless, it is important to know up front that some treatments can cause temporary or permanent infertility.

A fertility specialist can explain your options for fertility preservation, the process of saving or protecting your eggs or reproductive tissue, to have biological children in the future. Options may include egg freezing (egg banking, egg cryopreservation or oocyte cryopreservation), embryo freezing (embryo banking or embryo cryopreservation), ovarian shielding (gonadal shielding), ovarian tissue freezing (ovarian tissue banking or ovarian tissue cryopreservation), ovarian transposition (oophoropexy) and radical trachelectomy (radical cervicectomy). Also, keep in mind that families are made in many ways, such as adoption and surrogacy.

Surgery

Early stages of cervical cancer are sometimes treated surgically with fertility preservation in mind. The risk of infertility is still present, so talk with your doctor before moving forward.

A cone biopsy removes a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix and cervical canal. If the edges of the cone have negative margins, meaning they do not contain cancer cells, you can be monitored without further treatment unless the cancer returns. If the edges of the cone biopsy have positive margins, meaning cancer cells are still present, you may be treated with another cone biopsy, simple hysterectomy, radical hysterectomy or a radical trachelectomy.

In a simple hysterectomy, the cervix and uterus are removed. In a radical hysterectomy, the uterus, tissue next to the uterus and the upper part of the vagina are removed. The ovaries and fallopian tubes are usually not removed though some advocate for removal of the fallopian tubes even when the ovaries are preserved. In some cases of very early cervical cancer, a simple hysterectomy will suffice.

.jpg)

A radical trachelectomy is performed through the vagina or the abdomen and is sometimes done laparoscopically (see Figure 1). This procedure is an option for some patients interested in fertility preservation. To check whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, the surgeon might remove some of the nodes at the same time as a trachelectomy or hysterectomy. This is known as a pelvic lymph node dissection or lymph node sampling.

Pelvic exenteration is the most extensive procedure used to treat cervical cancer, and it is reserved for certain recurrent cancers. This operation removes the same organs and tissues as a radical hysterectomy, along with lymph nodes and possibly the vagina, urinary bladder, rectum and part of the large intestine, depending on where the cancer has spread. This might require a permanent ostomy to redirect the bowel or bladder.

Radiation Therapy

High-energy X-rays or particles are often used to destroy cancer cells. Radiation therapy can be administered from outside or inside the body. It may also be used as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life in people with advanced cervical cancer.

External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) delivers radiation from outside the body. It is often combined with chemotherapy (called concurrent chemoradiation) because the chemotherapy makes the radiation more effective. EBRT may be used by itself if you cannot tolerate chemoradiation, cannot safely have surgery or choose not to have surgery. It can also be used to treat areas to which the cancer has spread.

Brachytherapy, also called internal radiation therapy, involves placing a source of radiation in or near the cancer. The radioactive material is placed in a device that goes in the uterus or, in cases where a hysterectomy has been performed, the vagina. Low-dose rate brachytherapy may require you to stay in bed in the hospital for a few days, with instruments holding the radiation source in place. High-dose rate brachytherapy is an outpatient procedure over several treatments. For each high-dose treatment, the radiation source is inserted for a few minutes and then removed. Most patients who require brachytherapy are candidates for outpatient high-dose rate treatment.

Drug Therapy

Referred to as systemic therapy because it travels throughout the body, drug therapy is used to destroy microscopic cancer cells thought to be hiding in other organs, such as the liver, abdomen, lungs and bones. It also helps to lower the risk of future metastatic cancer. It is given through an IV into a vein or a port in your body. It can also be given as an injection (shot), subcutaneously (injection into fatty tissue under the skin) or orally as a pill or liquid.

Chemotherapy may be used alone or with other types of treatment. For some stages of cervical cancer, chemotherapy is given with radiation therapy (called concurrent chemoradiation).

Targeted therapy kills cancer cells or stops the progression of disease by targeting gene abnormalities, proteins or other substances that cancer cells need to survive and spread. The drugs travel throughout the body via the bloodstream looking for specific proteins and tissue environments to block cancer cell signals and restrict the growth and spread of cancer. Some of these drugs may be given alone or in combination with other drug therapies.

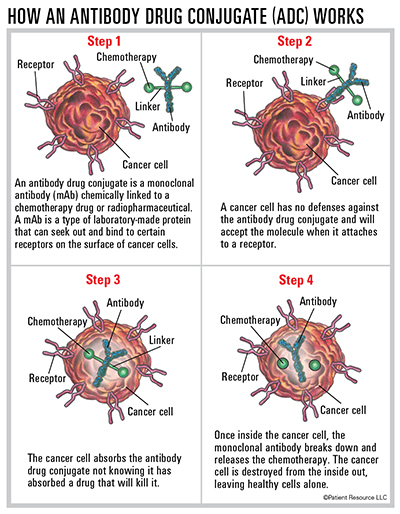

A type of targeted therapy known as an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) is a monoclonal antibody or laboratory-made protein that targets specific tumor antigens found on cancer cells and is chemically linked to a toxin, such as chemotherapy. The antibody attaches to cancer cells, so that the chemotherapy can be brought directly to the cancer cell, sparing most healthy cells. It gets swallowed by the tumor cell and breaks down inside the cell, releasing the chemotherapy drug, preventing growth signals and causing cell death. It may also stimulate the immune system. The most recent therapy approved to treat cervical cancer is an ADC.

Immunotherapy harnesses the potential of the body’s own immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors prevent the immune system from slowing down and help it to better recognize cancer cells as something foreign in the body. They target and block PD-1 or PD-L1, a checkpoint protein on immune system cells called T-cells. PD-1 normally helps keep T-cells from attacking other cells in the body, including some cancer cells. The immune checkpoint inhibitor approved to treat cervical cancer blocks PD-1 and boosts the immune response against cancer cells, which can shrink some tumors or slow their growth.

Clinical Trials

Most of the advances made in treating all types of cancer today were once therapies or procedures in the clinical trials process. They may offer life-saving treatments that are otherwise not available. Ask your doctor if you should consider a clinical trial. Your participation could contribute to the future of cancer care by being a critical component of cervical cancer research.

Understanding HPV

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a sexually transmitted infection that causes cervical cancer. More than 200 types of HPV exist, and about 40 types can be spread through sexual contact from the skin and mucous membranes (lining of the mouth, throat or genital tract). It is so common that most people – women and men – acquire an HPV infection at some point in their lifetime. Although most people clear the infection naturally through their own immune system (often without symptoms), long-term unresolved infections may lead to the development of cervical cancer. Two high-risk types, HPV 16 and HPV 18, cause most cervical cancers worldwide. HPV is also linked to anal, penile, vaginal, vulvar and throat cancers.

HPV Screening

Regular screening is essential to identify high-risk HPV strains – especially types 16 and 18 – before any cell changes occur. This allows for earlier intervention and monitoring, which helps with cervical cancer prevention.

HPV Vaccination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend routine HPV vaccination for girls and boys at age 11 or 12 and can be given starting at age 9. It offers the most protection when given before a person becomes sexually active. For young people not vaccinated within the age recommendations, HPV vaccination is recommended up to age 26.

Three vaccines are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for male and female children and young adults, 9 to 26 years old, to provide protection against new HPV infections and include:

- Gardasil (Human Papillomavirus Quadrivalent [Types 6, 11, 16, and 18] Vaccine, Recombinant).

- Gardasil 9 (Human Papillomavirus 9-valent Vaccine, Recombinant). Gardasil 9’s approval was recently expanded to include males and females ages 27 through 45 years.

- Cervarix (Human Papillomavirus Bivalent [Types 16 and 18] Vaccine, Recombinant).

The HPV vaccine does not treat existing infections or disease, and those who are already sexually active may benefit less from the vaccine because they may have been exposed to some of the HPV types the vaccine targets. Adults between the ages of 27 and 45 may decide to get it after talking with their doctor about their risk of new HPV infections.